The rapid rise of protein language models and generative AI has opened the door to a bold new frontier in synthetic biology: designing novel proteins from scratch using only computational tools. Among the most compelling applications is the creation of mini-protein binders: small, stable proteins that can latch onto a biological target with high specificity, offering potential as therapeutics, diagnostics, or research tools.

In this project, I set out to design a de novo mini-protein binder for the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain (RBD), the same region that allows the virus to enter human cells by interacting with the ACE2 receptor. This interface has been extensively studied and serves as a well-defined benchmark for computational protein design.

But rather than relying on known binders or sequence motifs, my goal was more ambitious: to build a binder from scratch, using an end-to-end generative pipeline made entirely of open-source tools. The project draws inspiration from cutting-edge techniques like diffusion-based structure generation, sequence design with deep learning, and structure prediction via AlphaFold2, all culminating in in silico docking and structural validation.

Here’s the core pipeline I implemented:

-

Backbone generation using RFdiffusion, a generative model for protein structures.

-

Sequence design for the generated backbones using ProteinMPNN, a deep learning model that maps structures to likely sequences.

-

Folding prediction with Boltz2 to ensure structural viability and stability of the designed proteins.

-

Docking to the SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD using LightDock, to assess binding potential at the ACE2 interface.

The final result is a collection of entirely novel mini-proteins, i.e., short sequences that are predicted to fold into compact, stable structures and potentially bind to the viral RBD. This project demonstrates not only the power of modern AI tools in synthetic biology, but also how individuals outside of traditional wet labs can now explore therapeutic design using open data and open models.

In the rest of this post, I’ll walk you through each step in the pipeline, share design choices and results, and reflect on the challenges and opportunities in this emerging space.

1. Backbone generation: RFDiffusion with ACE2 Hotspot constraints

The first step in the pipeline was to generate candidate binder backbones that are geometrically compatible with the SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD, and in particular with the ACE2 binding site. For this, I used RFdiffusion, a diffusion-based generative model for protein structures that can build new backbones in the context of a fixed target protein and optional interface constraints (“hotspots”).

Defining the design problem

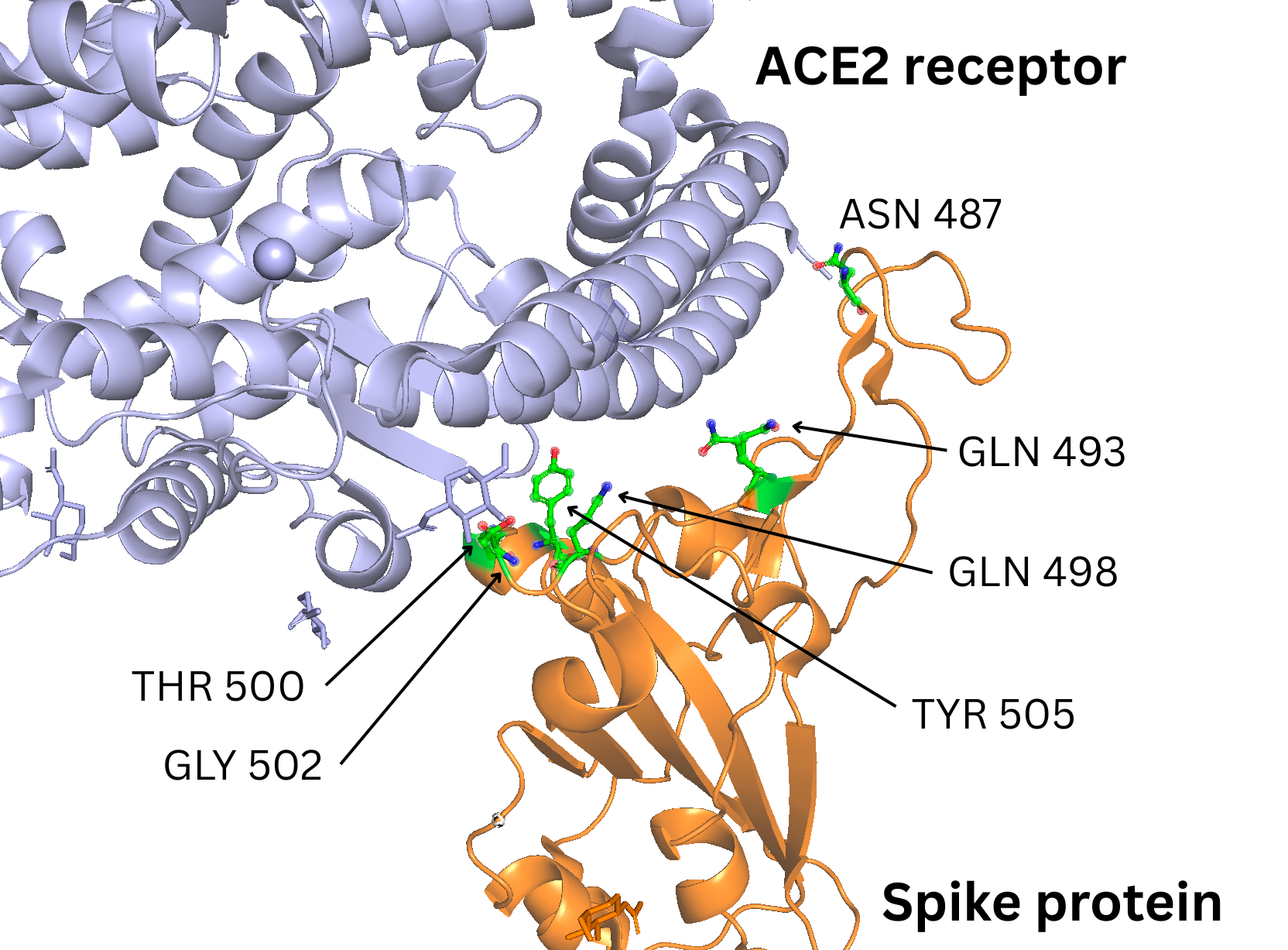

I started from a high-resolution structure of the SARS-CoV-2 RBD bound to human ACE2, focusing specifically on the region of ACE2 that contacts the viral RBD. To bias the designs toward biologically meaningful interactions, I relied on the hotspot analysis from Veeramachaneni et al. (“Structural and simulation analysis of hotspot residues interactions of SARS-CoV-2 with human ACE2 receptor”).

From this study, I selected six ACE2 hotspot residues that contribute strongly to RBD binding:

-

THR500

-

GLY502

-

TYR505

-

GLN498

-

GLN493

-

ASN487

These residues sit at the heart of the ACE2–RBD interface, forming a dense network of hydrogen bonds and van der Waals contacts with the spike protein. In RFdiffusion, I treated them as target-side hotspots: positions on the RBD surface where the model is encouraged to place complementary binder residues.

Figure 1: ACE2 receptor - Spike Protein RBD interaction interface with highlighted hotspots selected for RFDiffusion design.

Figure 1: ACE2 receptor - Spike Protein RBD interaction interface with highlighted hotspots selected for RFDiffusion design.

RFdiffusion setup

Conceptually, the RFdiffusion setup looked like this:

-

The RBD structure is held fixed as the “target”.

-

A new binder chain is initialized near the ACE2 interface and allowed to diffuse (i.e., evolve) into a structured backbone.

-

The hotspot residues on the RBD are passed to the model so that it preferentially forms contacts in their vicinity.

Rather than copying the ACE2 sequence or structure directly, the idea was to let RFdiffusion invent entirely new scaffolds that nonetheless “hug” the same region of the RBD that ACE2 uses. In practice, this means we’re asking the model:

“Generate a small, stable backbone that packs against this specific patch of the RBD and makes good contacts with these hotspot residues.”

I ran 10 independent RFdiffusion trajectories, each allowed to generate a candidate mini-protein backbone in the presence of the RBD and hotspot constraints.

What RFdiffusion actually produced

The 10 trajectories naturally fell into two qualitative categories:

Single-chain designs with a dangling tail

In most runs, RFdiffusion produced a single, relatively long chain that contained a compact interface region plus an extended segment sticking out into solvent. That extra segment was clearly non-interacting: no meaningful contacts with the RBD, just a flexible-looking tail. While these are technically valid structures, they are not ideal as mini-protein binders: they’re larger than necessary and potentially less stable and harder to express.

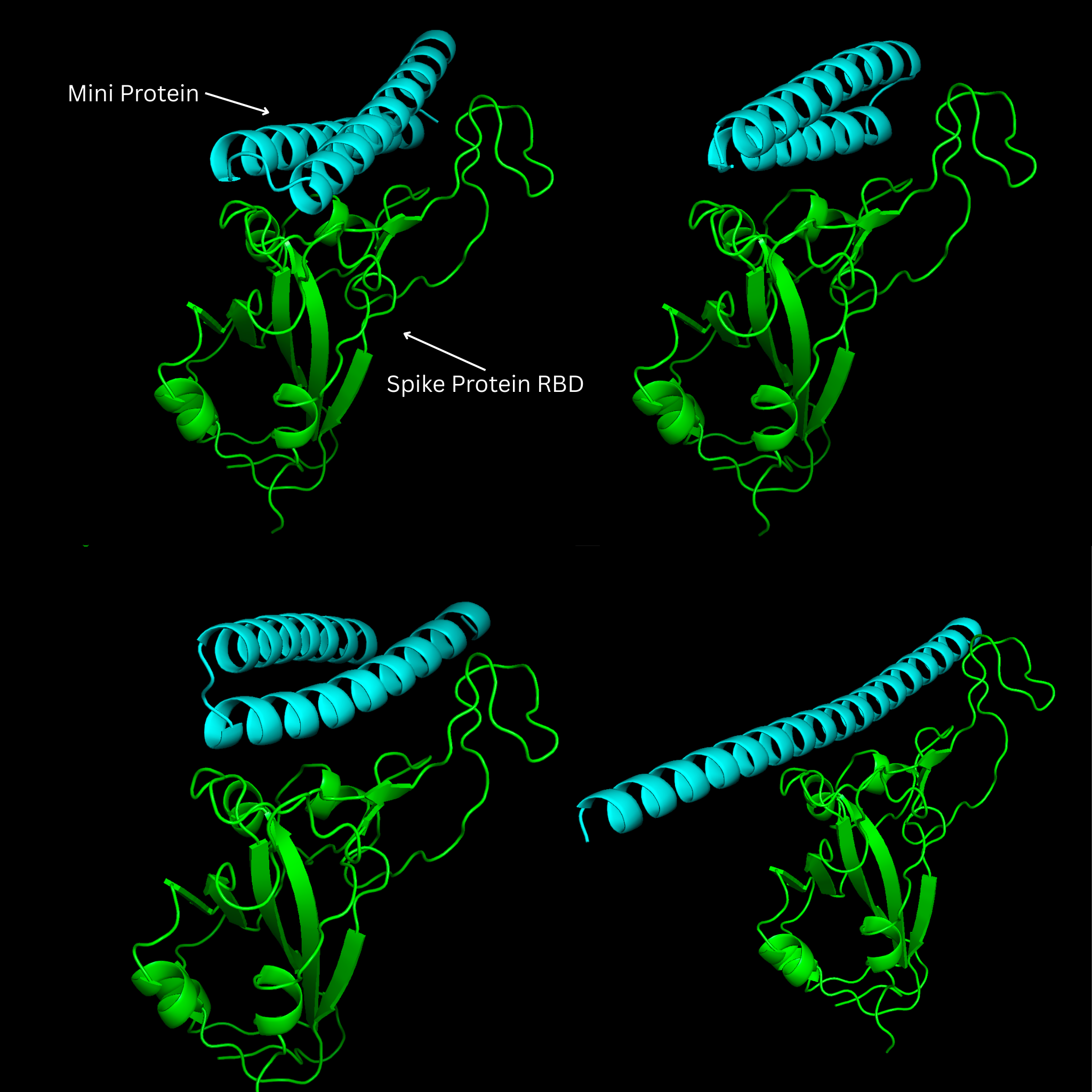

Compact two-helix designs at the interface

In three runs (design 1, 4, and 7), RFdiffusion generated short, compact backbones made of two α-helices arranged against the RBD surface. These helices qualitatively resemble the ACE2 helical segment that engages the spike protein, but are not copies; they’re de novo scaffolds that happen to occupy a similar part of structural space. Importantly, in these designs the helices sit directly over the ACE2–RBD interface, making close approach to the hotspot residues defined above.

Figure 2: Several designs were a single relatively long alpha helix. Most of the protein sticking out into solvent, not interacting with the spike protein

Figure 2: Several designs were a single relatively long alpha helix. Most of the protein sticking out into solvent, not interacting with the spike protein

Selecting the top backbones

For a first pass, I used simple, qualitative criteria to select promising candidates:

-

Compactness: no long unstructured tails or obvious “dead” regions far from the RBD.

-

Interface placement: the backbone should sit snugly over the ACE2 binding patch on the RBD.

-

Hotspot engagement (visual): the generated helices should appear to make contacts across the hotspot region, rather than drifting to some unrelated patch of the surface.

Based on these criteria, I discarded the “single long chain with a dangling tail” designs and kept designs 1, 4, and 7 as the top three backbones for further work. These three candidates provided the right balance of: small size (mini-protein-like), clear interface geometry, and ACE2-like orientation at the RBD surface.

In the next step, I took these three backbones into ProteinMPNN to design amino acid sequences that could plausibly fold into these shapes while maintaining their interface contacts to the spike RBD.

2. Inverse folding with ProteinMPNN: from structure to sequence

With the three most promising RFdiffusion backbones in hand (designs 1, 4, and 7), the next step was inverse folding: assigning amino acid sequences that are compatible with each backbone’s 3D geometry. For this, I used ProteinMPNN (pMPNN), a deep learning model trained to predict realistic protein sequences given fixed backbone coordinates.

Conceptually, this step answers a simple but crucial question:

If this backbone were a real protein, what sequences could stably fold into it?

ProteinMPNN setup

I ran ProteinMPNN using its default parameters, without adding any residue-level constraints or biases. The goal here was not to over-engineer the design, but to let the model freely explore sequence space given the structural information encoded in the backbone.

A deliberate simplification in this stage was that I did not force the first residue to be methionine (M). From a biological and experimental perspective, this would of course be required for expression in most systems.

However, this project is entirely in silico, and at this stage, I was primarily interested in validating the pipeline logic, rather than producing expression-ready constructs.

In a follow-up iteration aimed at wet-lab validation, this constraint could easily be added either directly in pMPNN or later during construct design.

Generating sequence diversity

For each of the three selected backbones, I sampled 4 independent sequences, resulting in a total of 12 candidate mini-protein binders.

Sampling multiple sequences per backbone is important for two reasons:

-

Robustness, if a backbone is viable, there should be many sequences that can realize it, not just one.

-

Interface exploration, different side-chain patterns on the same scaffold can lead to different interaction modes with the RBD, potentially affecting affinity and specificity.

Even without explicit interface constraints, ProteinMPNN tends to produce sequences with sensible biophysical properties: compact hydrophobic cores within the helices, and more polar or charged residues exposed to solvent and the binding interface.

Scope and limitations

At this stage, the output sequences should be viewed as candidate realizations of the designed backbones, not optimized binders. I did not:

-

Enforce specific residue identities at the RBD interface

-

Bias toward known ACE2-like motifs

-

Optimize for expression, solubility, or aggregation resistance

All of these would be natural next steps in a more mature design cycle. Here, the objective was simpler: verify that clean, compact two-helix backbones produced by RFdiffusion can be populated by realistic sequences using an off-the-shelf inverse folding model.

In the next section, I move from sequence design to structural validation, using Boltz2 (as an AlphaFold alternative) to check whether these sequences actually fold back into their intended geometries and remain compatible with the original binder design.

3. Folding validation with Boltz2: good vs bad alignments

With sequences in hand, the next step was to ask a crucial question: do these designs actually fold the way they’re supposed to? To answer this, I used Boltz2 for structure prediction.

For each of the 12 designed sequences (4 per backbone × 3 backbones), Boltz2 produced four structural models, saved as model_0 through model_3. I won’t speculate here on the exact meaning of these model indices, but in practice they represent alternative folding hypotheses for the same sequence.

What matters is that not all models are equally good.

Comparing predicted folds to the designed backbone

To evaluate the results, I aligned each Boltz2-predicted structure to its original RFdiffusion backbone and visually inspected the overlap. This allowed me to distinguish between two very different outcomes:

-

Good folding predictions, where the mini-protein adopts a structure that closely matches the designed backbone and sits in the expected position relative to the RBD.

-

Bad folding predictions, where the protein is still folded but is dramatically mispositioned, often rotated or shifted away from the intended binding interface.

Rather than exhaustively showing all 48 Boltz2 outputs (12 sequences × 4 models), I selected two representative examples to illustrate the contrast.

A “good” alignment

In the first example, the predicted structure overlays cleanly with the original backbone:

-

The two helices are preserved.

-

The overall geometry matches the design.

-

The RMSD is below 0.9 Å, with only minor local displacements.

The aligned structures can be explored in the 3D image below:

These small deviations are entirely expected and even reassuring: they reflect the natural flexibility of helices and side-chain packing differences, rather than a failure of the design. Qualitatively, this is exactly what you hope to see when validating a de novo mini-protein: the sequence folds back into the intended scaffold.

A “bad” alignment

In the second example, the contrast is stark. Although the protein still forms secondary structure, the binder is dramatically rotated relative to the expected position. When aligned to the same reference:

-

The backbone no longer overlaps with the designed scaffold.

-

The helices are displaced away from the ACE2-like interface.

-

The binder is clearly incompatible with productive binding to the RBD.

Again, the structures can be explored in the 3D image below:

This kind of failure mode is important to highlight. It shows that a predicted fold can look “reasonable” in isolation, yet still be completely wrong in the context of a binding task.

### Why this comparison matters

These two figures are not meant to be statistically representative or exhaustive. Instead, they serve a simpler purpose: to visually define what success and failure look like in this pipeline.

A low RMSD, clean overlap, and correct orientation relative to the target are strong indicators that the sequence–structure pair is viable. Large rotations or displacements, even if the protein appears folded, are a red flag for downstream binding and docking steps.

This step turned out to be a critical filter in the pipeline: before worrying about docking scores or interface energetics, it’s essential to first confirm that the designed sequences can reliably realize the intended backbone geometry.

In the next section, I’ll build on this validation step and show how these filtered designs were taken forward for docking and interface assessment against the SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD.

4. Docking to the SARS-CoV-2 RBD: validating binding geometry

After validating that the designed sequences could reliably fold back into their intended two-helix backbones using Boltz2, the final step was protein–protein docking. This ordering is intentional and important.

Why docking after folding validation

Docking only makes sense once you’ve established that:

-

The designed sequence can actually realize the intended backbone, and

-

The resulting structure is stable and well-defined.

Without this step, docking scores and poses can be misleading: a poorly folded or misfolded binder may still produce apparently reasonable docking solutions simply because the docking algorithm compensates by rotating or deforming the complex. By validating folding first, docking becomes a test of binding compatibility, not a rescue attempt for bad structures.

In other words, the question at this stage is no longer “can this sequence fold?”, but rather: “Given that it folds correctly, does it bind the right place in the right way?”

Docking setup and rationale

I used LightDock, treating the spike RBD as the receptor and the designed mini-protein as the ligand. Docking was performed under the following guiding principles:

-

Local docking at the ACE2 interface. Active residue restraints were applied on the RBD to focus sampling on the ACE2 binding patch, reflecting the original design hypothesis.

-

Rigid-backbone docking. Backbone flexibility was disabled for both proteins. This was a deliberate choice: only designs that bind correctly without backbone distortion were considered viable. This makes docking a stricter and more informative filter.

-

Minimal bias on the ligand. Ligand restraints were either omitted or limited, allowing the binder to explore orientations freely while still targeting the correct region of the RBD.

LightDock performed hundreds of independent local docking searches (“swarms”) around the receptor surface, each converging to a best-scoring pose. The top-ranked poses across all swarms were then collected and analyzed.

Interpreting the docking results

After energy minimization, the top five docking solutions showed strong overall agreement:

-

Four models aligned closely, differing only by minor displacements consistent with small rigid-body adjustments.

-

One model showed a larger displacement, but still remained clearly anchored to the correct ACE2 interface region.

Figure 3: Top 5 docking results (after energy-minimization). One of the 5 configurations shows a mini-protein significantly shifted, but still in the correct binding-region.

Figure 3: Top 5 docking results (after energy-minimization). One of the 5 configurations shows a mini-protein significantly shifted, but still in the correct binding-region.

Crucially, there was no evidence of alternative binding sites dominating the top rankings. Instead, the best-scoring poses consistently converged to the same region of the RBD, with similar orientations of the mini-protein relative to the interface.

This kind of convergence is far more meaningful than any single score. It suggests that the designed binder is not just compatible with the ACE2 interface in one lucky pose, but that multiple independent docking searches recover the same binding geometry.

What docking does (and does not) prove

It’s important to be clear about the scope of these results.

Docking here does not prove:

-

Binding affinity

-

Kinetics

-

Experimental viability

What it does show is that:

-

The designed mini-protein can fold as intended

-

The folded structure is geometrically compatible with the ACE2 binding site

-

The binding mode is reproducible and structurally plausible

Taken together, these steps form a coherent in silico validation chain: design → sequence → folding → docking.

Final thoughts

This project was intentionally scoped as an end-to-end, open-source, computational exploration of de novo mini-protein binder design. Starting from nothing more than a target structure and literature-derived hotspots, the pipeline produced entirely novel proteins that:

-

adopt compact, stable folds,

-

resemble known binding motifs without copying them, and

-

consistently dock to the intended functional interface.

There is plenty of room for improvement: from tighter interface optimization and explicit affinity design, to experimental expression and validation, and that’s exactly what makes this space exciting.

If you have suggestions, critiques, or ideas for how this pipeline could be improved or extended, I’d genuinely love to hear them. And if you found this walkthrough interesting or useful, feel free to share the post on LinkedIn; conversations and feedback are what push these projects forward.

Thank you. Emanuele